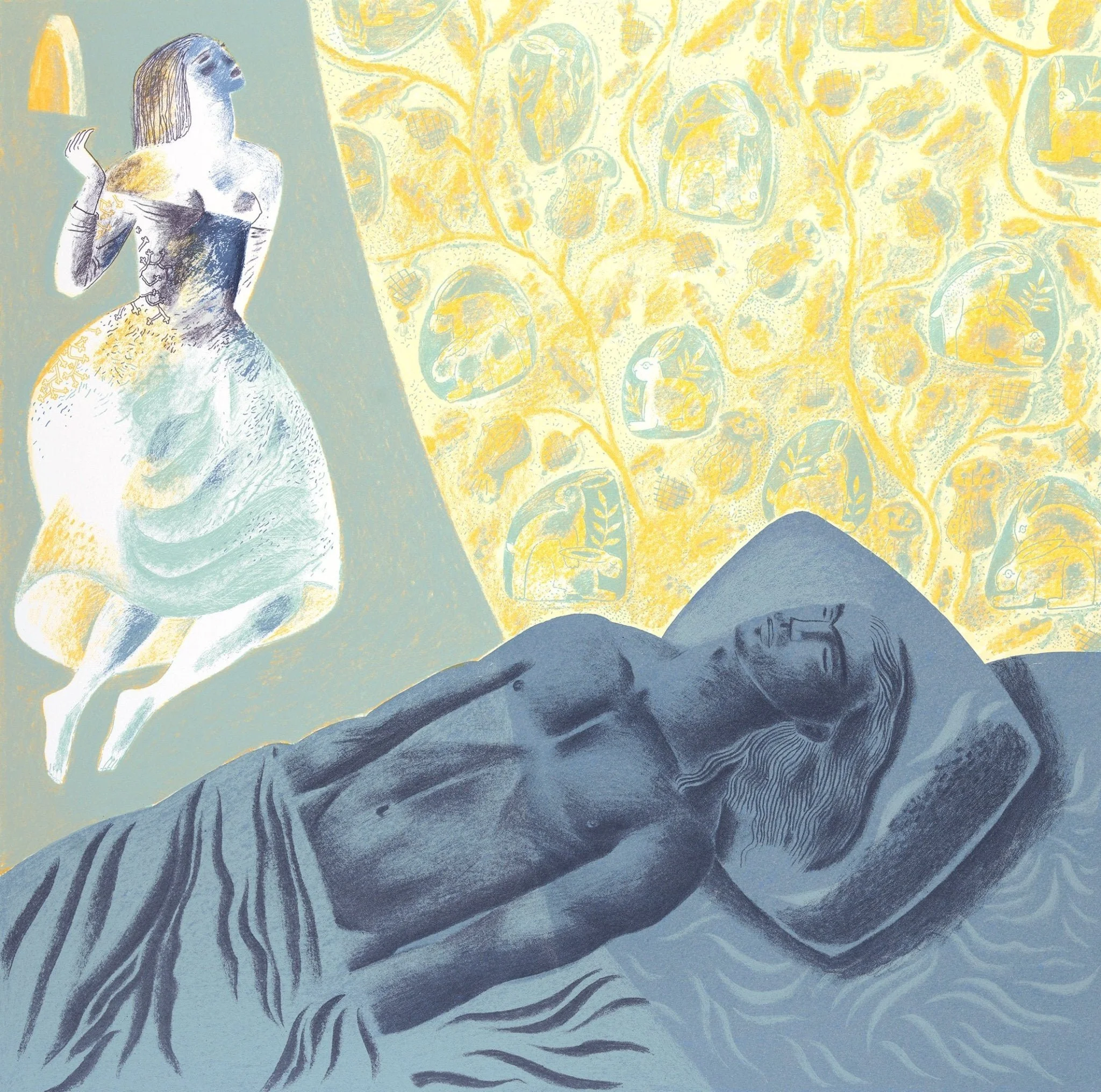

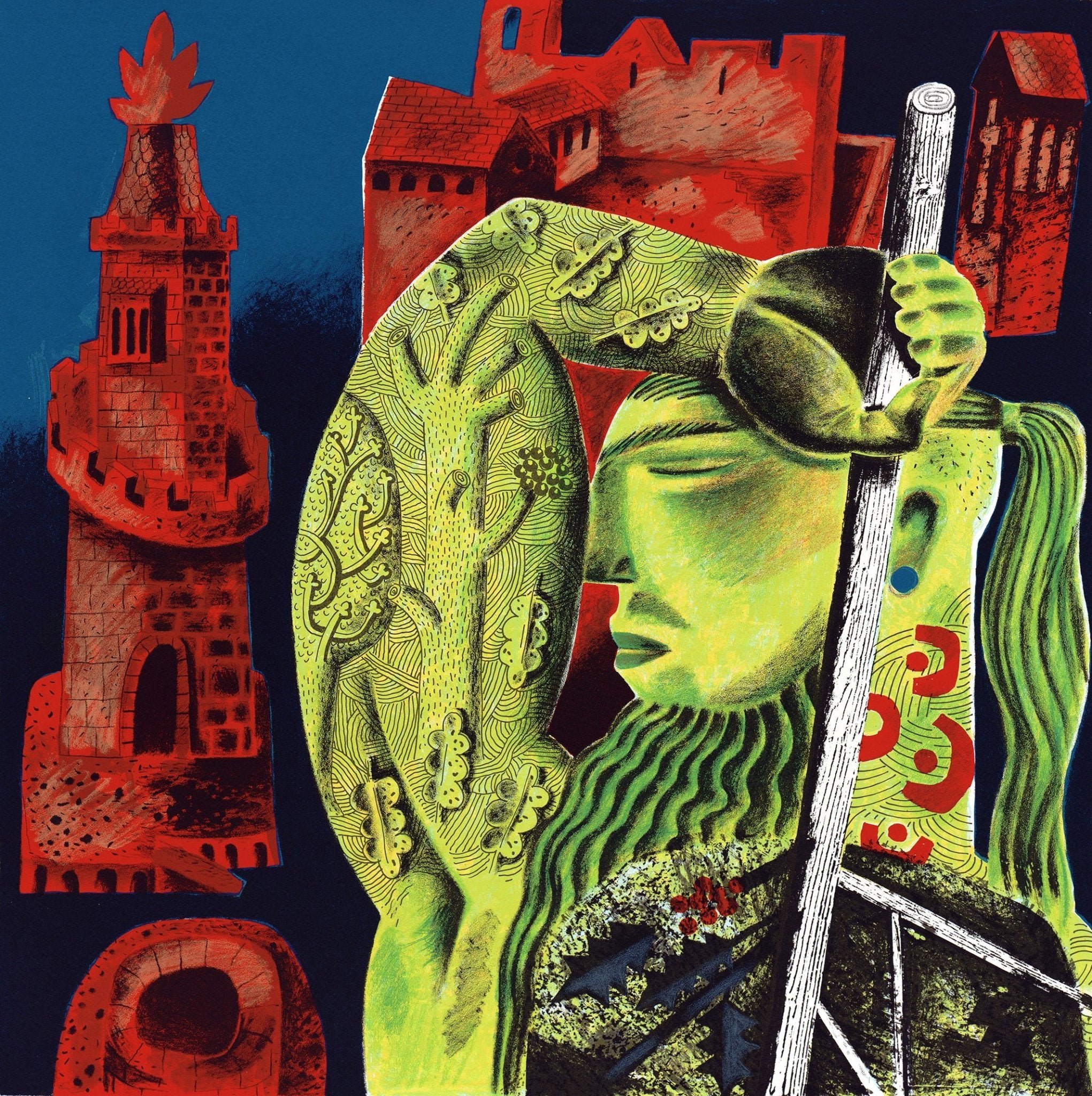

Gawain & The Green Knight

Clive Hicks-Jenkins

"Over the past twenty-five years, Clive Hicks-Jenkins has achieved renown in his native Wales and beyond as a painter of rare and powerful vision. It helps that he came to painting by an unusual route, having enjoyed a successful theatrical career - as actor, director, choreographer and stage designer – before the urge to paint became irresistible. Today his paintings of figures and animals are so striking, at least in part, because of the continual dialogue between design and dance, structure and movement”

Clive Hicks-Jenkins

Clive’s complex creative process enhances this effect. If, for example, he is due to paint a horse, he will first draw the animal, then create a cardboard maquette from the drawing, articulating this model in such a way that its head, torso and limbs can be placed in positions impossible for even the most agile horse. Painting from such a maquette gives Clive control over the composition (and the vital balance between positive and negative space), while at the same time adding emotional expression and that feeling of suppressed movement. The resulting tension is less that of a coiled spring as of a spring caught in the moment of uncoiling.

This dynamism suits Clive’s penchant for narrative painting. In series after series he has explored the interactions of characters famous and obscure, from St George and the dragon to Hervé (a blind Breton monk) and his wolf companion. He takes inspiration from religious stories, Welsh legends, modern drama and medieval verse. The characters of Sir Gawain, his horse Gringolet, the Green Knight and the rest have haunted his imagination for years, but something about the multi-layered intricacy and artifice of the poem suggested printmaking rather than painting.